An Island in 3D

Background

The understanding and precise mapping of spatial relationship between organisms and their environment is vital to protect them. Humanity has always strived to describe and map their environment, but up until recently, only in 2 dimensions.

Recent advances in technology allows us to ‘3D-scan’ entire ecosystems, and implement ecological data through predictive mathematical models. And display them in immersive VR systems. The potential is unparalleled.

Aim

This study aims to determine and test methodology to 3D render large scale environments, I this case the island of Phangan and its surrounding reefs, and implement 7 years worth of ecological baseline parameters.

Methods

The data is collected by underwater camera transects, and unmanned aerial vehicles (Drones). The resulting images are converted to 3 dimensional models via cloud computing and ported to current VR and 2D desktop systems, geo-referenced via GIS.

%

Project Progress

Sectors scanned

Pomacentridae recruitment and their role in filamentous algae turf control in coral reefs in the Gulf of Thailand

Background

Coral reef ecosystems are currently under threat at unprecedented levels from frequently raised sea surface temperatures, elevated nutrient levels, and unsustainable fishing practices. To predict and mitigate negative effects on environment and coastal populations, the understanding of internal processes in coral reefs are key, but south east Asian ecosystems are notoriously understudied, in comparison to Caribbean or Australian areas. Algae, the main competitor of Scleractinia for space and light, has already replaced coral as the dominating organism in many reef ecosystems. Algae cover is primarily controlled by nutrient and light availability, P:N ratios, and herbivory (Vermej et al, 2010). South East Asian reefs are generally characterized by high filamentous algae turf-, and lower macro algae-cover (src), contrasting their counterparts in the aforementioned locations. Coastal reefs in the Gulf of Thailand, which are considered eutrophied from untreated effluent and agricultural run-off (Cheevaporn et al, 2003), are additionally portrayed as high in Damsel Fish (Pomacentridae) abundance, and low in ‘classical’ browsers like Unicorn Fish (Naso spp., Acanthuridae) (Puk et al, unpublished).While macro algae control, and even phase-shift removals by macro-algae browsers and –grazers are well described (Graham et al, 2013; Idjadi et al, 2003), our understanding turf algae croppers in the Indo-Pacific, and the role of territorial Pomacentridae in algae cover control remains limited..

Aim

For this study, we propose a simple set of manipulation experiments to increase our knowledge of how territorial Pomacentridae are recruited to fresh substrate, and their influence and control of turf algae cover.

Research Questions:

- How fast do damsel fish accept and defend new territories?

- What influence does the absence/ presence of DF have on algal turf?

- What influence does the absence of roving herbivores have on DF behavior and algal turf efficacy?

Methods

Triplicates of 4 different plot designs will be place and fastened directly on the sand in relatively sheltered positions in Damselfish territory at 3-4m depth. Each plot is stacked with 12 tiles, one of which will be removed monthly to measure algae dry weight, scraped from the tiles. The tiles are attached to 4kg cinder blocks, which act as anchors for each plot.

- Plot A: open design, allows access from all organisms in the reef.

- Plot B: fully caged design, allows access for organisms smaller than 5mm (i.e. crustaceans). This equates full herbivory exclusion.

- Plot C: medium mesh plot design, allows access for fish smaller than 4 cm, which equates access for Damsel Fish and neonates only.

- Plot D: caging control plot design, to correct experiment for light and hydrodynamic effects

Nutritional status of reef-associated fishes attracted by Fish Aggregation Devices in comparison to fishes found on natural reefs, in the Gulf of Thailand

Background

The fish aggregating properties of structures submerged, or drifting in the ocean have been known and used by fishermen for centuries. It has been proposed that fish are attracted to floating or stationary objects, as they provide ‘visual stimulus in the optical void’.

Since global fish stocks are in steady decline, measures to rejuvenate fish populations, and their financial yield are increasing. In 2013, four metal structures were deployed near the shores of Koh Phangan to further the local fishing efforts.

Recent research indicates, that artificially aggregated fish find little to no food at floating structures, implying a lower quality of life for fish, but studies on permanent structures are still inconclusive.

Aim

This study aims to determine whether the nutritional status of fish located at artificial reefs differs from the population of natural reefs. Results will indicate whether the structures can (a) aggregate fish, and (b) supply ample food for these fish, to make a meaningful contribution to local fish conservation efforts.

Methods

The data is collected by visual underwater surveys. On natural reefs, Belt Transect Surveys are conducted; whereby this method is adjusted for the artificial reefs for better comparison. All the fishes observed on the transects are first identified to species level. Subsequently the species are divided into length-categories, which are used for the length-weight formula to estimate the weights of the individual fish.

%

Project Progress

Fish Surveys

Fish counted (est.)

Shark encounters

Comparative evaluation of ecosystem services provided by artificial reefs in the Gulf of Thailand

– Associated fish communities, their functional diversity and biomass

Background

Coral reefs today are simultaneously threatened by anthropogenic local and global stressors. Coastal human population depends on reefs as natural sources of food and income. The value of coral reefs worldwide have been estimated as US$ 30 billion in net benefits of goods and services. Therefore, the protection of these ecosystems benefits social and economic development. A potential measure is the use of artificial reefs to enhance fish production and other reef ecosystem resources. Under the Artificial Reef Program of the Department for Marine and Coastal Resources (DMCR) in Thailand have deployed hard structures in coastal waters since 1978 to create fishing grounds. But until now, the effectiveness in terms of habitat provision and fish production of the installed artificial reefs regarding structure type and material has not been sufficiently assessed.

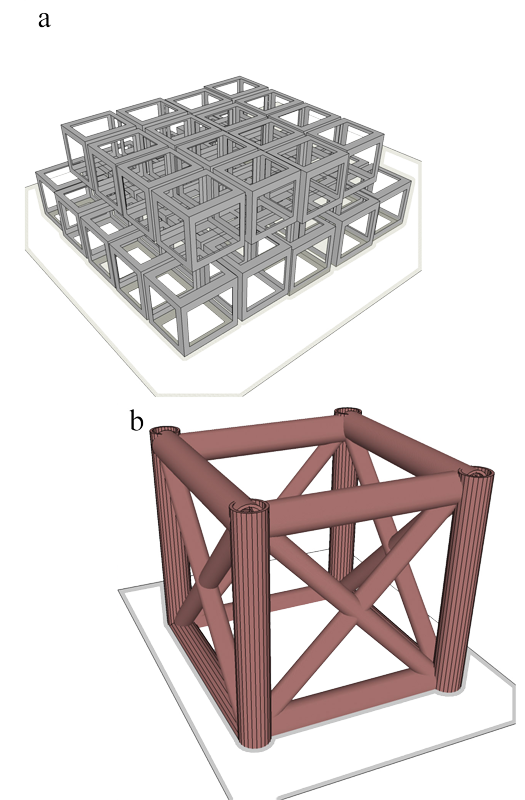

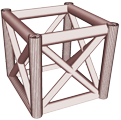

At the study site Koh Phangan 11 structures serve as artificial reefs since 2013. Around the island, seven concrete dice aggregations have been deployed in depth of around 20 meters the bays of Haad Khom, Chaloklum, Mae Haad, Haad Yao, Ban Thai and Thong Nai Pan, as well as four structures made of metal cubes in Haad Khom and Chalokum. Yet, the effect on community structure and diversity of benthos and fishes is unknown.

Aim

Results will help to compare the benthic and pelagic development of two different types of artificial reef structures with natural reefs as well as the the surrounding environment without artificial structures. Further, it may allow to determine the effectiveness of artificial reefs compared to natural reefs in terms of fish production and habitat provisioning.

The findings will help to estimate the economic value and the benefit for the local stakeholders and communities.

Results will finally be used to give advice about further artificial reef deployment, such as favourable structure material, structure type and which environmental factors are needed to be considered to support the development of a productive artificial coral reef.

Methods

Background data to be assessed are Volume, Area covered, Depth Range, Complexity, Texture and composition, Location, Light Availability, Surrounding Habitat, Turbidity, Surface, Deposition date.

Data about fish assemblage is conducted via visual underwater surveys. These are adapted to the natural reef sites and to the artificial reef sites respectively. On the natural reef sites, the most suitable method is the Belt Transect Survey, for artificial reefs this method is adapted to the structural set-up of the reef. Both methods allow a ratio of species number per square meters and biomass per square meter, which makes it easier for us to compare the sites.

Comparative evaluation of ecosystem services provided by artificial reefs in the Gulf of Thailand

– Associated benthic communities, their succession and primary production

Background

Healthy coral reef ecosystems provide important ecosystem services to humans. They are priceless as a food source for millions of people contributing roughly 10% to the world’s fish catches.

However, coral reefs are threatened from global- and local stressors, and already one third of the reefs have died off (Hughes et al., 2003). Over half of the remaining reefs are at risk and considered as threatened (Hughes et al., 2003). Artificial reefs are defined as “submerged structures placed on the seabed deliberately, to mimic some characteristics of natural reefs” (EARRN; see Jensen, 1997). Their traditional application has focused on enhancing fish abundance and total fish catch for recreational and commercial fisherman in coastal waters, but recent evaluations suggest that they can be utilized to compensate for structural damage to natural habitat and restore productivity where habitat is lost or destroyed (Pickering et al., 1998).

Aim

The aim of this project is to study the recruitment and succession pattern, and the associated primary production, of two different artificial structures (concrete and metal) compared to natural reefs.

Primary production is a key ecosystem service as it produces the energetic base of most food webs in the aquatic environment (Valiela, 1995; Chapin et al., 2011).The production at higher trophic levels will depend on the production at lower levels (bottom-up control).

By assessing the role of ARs in enhancing primary production and energy transfer to the lower trophic levels of the benthic food web (Leitão 2013) we can determine the ecological implications of these reef structures.

Method

The recruitment and succession of organisms on the different structures will depend on the environmental conditions at each location as well as on the material used for the ARs. To be able to analyse these effects we will deploy a series of settlement tile structures (PVC frame with a mesh where terracotta tiles will be attached) that will act as new substrate for the recruitment of organisms. This will provide us with information on the effect of the environmental conditions.

To be able to study the effect of the different materials (concrete and metal vs. natural reef) we will clear and monitor an area of 10×10 cm on each location.

Background parameters such as temperature and light will be measured with the aid of loggers.

Settlement tiles will periodically be removed from each location and analysed at the laboratory, where incubation experiments will be conducted to measure respiration and primary production.

%

Project Progress

Settlement tiles deployed

Lux loggers installed

ARTIFICIAL

REEFS

Artificial reefs (AR) are underwater structures used in coastal management that offer additional hard substrate for reef-building organisms (Bohnsack & Sutherland, 1985). They are deployed to offer a range of ecosystem services such as increasing fishery yields and local species diversity, supporting coastal protection and as attraction for divers and recreational fishers. Recently they have become of particular interest in areas where natural reef systems are shifting to algae dominated states as a measure of restoration and environmental mitigation (Seaman, 2002). As they mimic natural reefs they offer a food source and a potential shelter for reef fish. Their structure often works as a barrier against fishing nets protecting local stocks from overfishing (Baine, 2001). Recent research has hinted that the protection of herbivores fish is crucial as they play a key role in controlling the benthic community in the Gulf of Thailand (Stuhldreier, Bastian, Schoenig, & Wild, 2015).

References:

Bohnsack, J. A., & Sutherland, D. L. (1985). Artificial Reef Research – a Review with Recommendations for Future Priorities. Bulletin of Marine Science, 37(1), 11-39.

Baine, M. (2001). Artificial reefs: a review of their design, application, management and performance. Ocean & Coastal Management, 44(3-4), 241-259. doi: Doi 10.1016/S0964-5691(01)00048-5

Seaman, W. (2002). Unifying trends and opportunities in global artificial reef research, including evaluation. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 59, S14-S16. doi: DOI 10.1006/jmsc.2002.1277

Stuhldreier, I., Bastian, P., Schoenig, E., & Wild, C. (2015). Effects of simulated eutrophication and overfishing on algae and invertebrate settlement in a coral reef of Koh Phangan, Gulf of Thailand. Mar Pollut Bull, 92(1-2), 35-44. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.01.007

ECOSYSTEM

SERVICES

“Ecosystem services are the direct and indirect contributions of ecosystems to human well-being. They support directly or indirectly our survival and quality of life.

Ecosystem services can be categorized in four main types:

Provisioning services are the products obtained from ecosystems such as food, fresh water, wood, fiber, genetic resources and medicines.

Regulating services are defined as the benefits obtained from the regulation of ecosystem processes such as climate regulation, natural hazard regulation, water purification and waste management, pollination or pest control.

Habitat services highlight the importance of ecosystems to provide habitat for migratory species and to maintain the viability of gene-pools.

Cultural services include non-material benefits that people obtain from ecosystems such as spiritual enrichment, intellectual development, recreation and aesthetic values.

Some examples of key services provided by ecosystems are described below:

Climate regulation is one of the most important ecosystem services both globally and on a European scale. European ecosystems play a major role in climate regulation, since Europe’s terrestrial ecosystems represent a net carbon sink of some 7-12% of the 1995 human generated emissions of carbon. Peat soils contain the largest single store of carbon and Europe has large areas in its boreal and cool temperate zones. However, the climate regulating function of peatlands depends on land use and intensification (such as drainage and conversion to agriculture) and is likely to have profound impacts on the soil capacity to store carbon and on carbon emissions (great quantities of carbon are being emitted from drained peatlands).

Water purification by ecosystems has a high importance for Europe, because of the heavy pressure on water from a relatively densely populated region. Both vegetation and soil organisms have profound impacts on water movements: vegetation is a major factor in controlling floods, water flows and quality; vegetation cover in upstream watersheds can affect quantity, quality and variability of water supply; soil micro-organisms are important in water purification; and soil invertebrates influence soil structure, decreasing surface runoff. Forests, wetlands and protected areas with dedicated management actions often provide clean water at a much lower cost than man-made substitutes like water treatment plants.”

Source: http://biodiversity.europa.eu/topics/ecosystem-services

PRIMARY

PRODUCTION

“Ocean productivity largely refers to the production of organic matter by “phytoplankton,” plants suspended in the ocean, most of which are single-celled. Phytoplankton are “photoautotrophs,” harvesting light to convert inorganic to organic carbon, and they supply this organic carbon to diverse “heterotrophs,” organisms that obtain their energy solely from the respiration of organic matter. Open ocean heterotrophs include bacteria as well as more complex single- and multi-celled “zooplankton” (floating animals), “nekton” (swimming organisms, including fish and marine mammals), and the “benthos” (the seafloor community of organisms).

The many nested cycles of carbon associated with ocean productivity are revealed by the following definitions (Bender et al. 1987) (Figure 1). “Gross primary production” (GPP) refers to the total rate of organic carbon production by autotrophs, while “respiration” refers to the energy-yielding oxidation of organic carbon back to carbon dioxide. “Net primary production” (NPP) is GPP minus the autotrophs’ own rate of respiration; it is thus the rate at which the full metabolism of phytoplankton produces biomass. “Secondary production” (SP) typically refers to the growth rate of heterotrophic biomass. Only a small fraction of the organic matter ingested by heterotrophic organisms is used to grow, the majority being respired back to dissolved inorganic carbon and nutrients that can be reused by autotrophs. Therefore, SP in the ocean is small in comparison to NPP. Fisheries rely on SP; thus they depend on both NPP and the efficiency with which organic matter is transferred up the foodweb (i.e., the SP/NPP ratio). “Net ecosystem production” (NEP) is GPP minus the respiration by all organisms in the ecosystem. The value of NEP depends on the boundaries defined for the ecosystem. If one considers the sunlit surface ocean down to the 1% light level (the “euphotic zone“) over the course of an entire year, thenNEP is equivalent to the particulate organic carbon sinking into the dark ocean interior plus the dissolved organic carbon being circulated out of theeuphotic zone. In this case, NEP is also often referred to as “export production” (or “new production” (Dugdale & Goering 1967), as discussed below). In contrast, the NEP for the entire ocean, including its shallow sediments, is roughly equivalent to the slow burial of organic matter in the sediments minus the rate of organic matter entering from the continents.”

Source: http://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/the-biological-productivity-of-the-ocean-70631104